“We basically had nothing through the growing season, and then for the first six months of this year, it just didn’t rain,” says Ollie Bevan, winemaker and viticulturist at Parea Estate and viticultural consultant at Growers Supplies. “In February, it was zero. I've never seen a month with 0.0 on it. There are always a few millimetres somewhere, but not a drop fell across the Barossa, Adelaide Hills or McLaren Vale.”

“There are just so many implications,” continues Ollie. “It’s really about crop load, crop health and balance. And it's not just what you see within the season. Crops are set the year before in the previous spring. If you have dry conditions during that period, it affects your crop the year later. There's a two-year domino effect.”

Anthony Koerner – father of Jono (Gullyview Estate) and Damien (Koerner Wine) – farms 70 hectares in the Watervale subregion of the Clare Valley. The 2024 vintage, though very dry, had the advantage of good soil moisture levels from the year prior. But there was no such advantage in the setup for this year, with 2024 the region’s second driest year on record.

“The start to 2025 is well below average and a long way from recharging subsoil moisture,” Anthony says. “We can supplement water with drip irrigation from the Murray via SA Water, but it can’t compensate for moisture from natural rainfall. Our soils are our best water reservoir when recharged from rainfall. The outlook for vintage 2026 is not good – we require some major rain events in the next four months.”

The story is not much different on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. “The harvest period that we've had was significantly drier than what we've seen in the most recent years,” says Garagiste’s Barnaby Flanders. “December onwards, over harvest, we had virtually no rain. A sprinkle here and there, but no significant rain.”

Those milder, warmer temperatures continued well into late April and May, he notes, with very mild and unseasonably warm late autumn weather. “We need to start replenishing water in the ground in late autumn and early winter, but we've kind of missed all that. We're now into July, and while we’ve had rain in the last couple of days… Well, we had a full day of rain yesterday, but it still only amounted to 16ml in the gauge.”

Regions where the water hasn’t historically been as much of an issue compared to the Barossa, for example, are now starting to feel the pinch. “I was at a workshop in the Adelaide Hills yesterday, and they're all panicking, because they've never seen anything like it,” says Ollie. “They've got five to 10 per cent of gum trees dying in their natural scrublands. They're worried, because they haven't seen these conditions before.”

While Ollie notes that McLaren Vale and the Barossa are more familiar with dry conditions, there are still significant hurdles. That’s made doubly challenging with the current low tonne prices for shiraz (which represents 65 per cent of the Barossa Valley’s plantings), making costly inputs uneconomic. “Unfortunately, water becomes capital… People are trying to buy it, trade it. It becomes more expensive. If you’re trying to buy extra megalitres, it adds up very quickly.”

“We don't irrigate our vines, so we are just relying on what falls out of the sky,” says Barnaby. “In vineyards where you are relying on irrigation water, if there are no winter rains to really fill up those dams, they are going to be back to being virtually zero or very low, and then you’d need to work out where you’re going to buy it from.”

Naturally, controlling rainfall is not an option, but Ollie believes that growers can adapt to be more resilient for future dry spells. “I think it all comes down to precision… More precisely watering sections of the vineyard that maybe need it more or less than other sections. Maybe you look at a mulch rotation. Mulch is expensive, but if you stagger it and budget for a third of your block each year, you can leave that section out every one in three waterings.”

Cover cropping is another strategy, but with species tailored to drier seasons, dying off at the right time to not compete with the vines, while providing organic matter for the soil and reducing evaporation and heat in the mid-rows. A deep investment in genuine sustainability and regenerative agriculture is key to the most progressive vineyards in the country, and perhaps the silver lining is a greater uptake of these practices.

“Drought has always been a problem,” Ollie concludes. “People may have to think about some details that maybe they haven't really needed to in the past. But I think that complex problems can be solved with precise and detailed thinking. There are plenty of solutions out there. It's just going to require a bit of effort.”

Join Halliday Wine Club to drink the very best of Australian wine

Are you an explorer, enthusiast or collector? No matter the Halliday Wine Club plan you choose, each month we'll deliver two bottles of 95+ point wines direct to your door. From $89 per month. You can skip, pause or cancel anytime. Join now.

Latest Articles

-

![Default article tile image]()

From the tasting team

Mike-Bennie-discovers-Wairarapa-NZ

11 hours ago -

![Default article tile image]()

From the tasting team

Sustainable and beyond: Marcus Ellis on sustainability in the wine industry

11 hours ago -

![Default article tile image]()

News

The reinvention of the Aussie sommelier

11 hours ago -

News

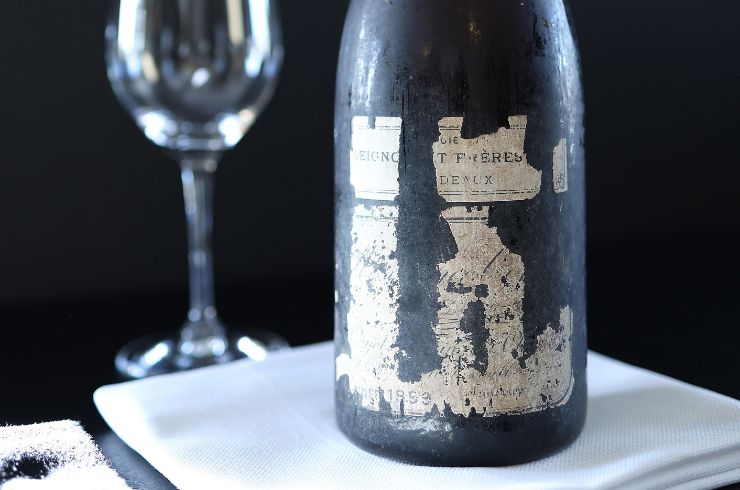

Why a co-owner of Bass Phillip decided to taste, instead of trade, this 127-year-old bottle of wine

1 day ago

More like this

-

From the tasting team

Marcus Ellis on why sugar shouldn't be a dirty word when it comes to riesling

22 May 2025 -

From the tasting team

Lead part or walk-on extra: Marcus Ellis on malbec

8 Apr 2025 -

From the tasting team

Is the term 'alternative' now redundant when speaking of grape varieties in Australia? Five wine experts give us their take.

20 Mar 2025