There is a golden rule when it comes to blending wine: the blend must be better than the individual components. Take two or more wines and the winemaker’s skill comes into play. Take 20, 40 or more parcels of wines, from many vintages, aged and nursed, over 10, 40, 50, 60 years or more, and you enter into the almost sacred realm of the master fortified winemaker.

The numbers are imposing by any measure, the task formidable, which is probably why today we see fewer Australian fortified winemakers than ever before. The market is small, the number of fortified experts is correspondingly small – and it is only getting smaller.

Is fortified winemaking intimidating? Well, let’s say it’s not for the faint-hearted.

Should the next generation of winemakers even be interested in pursuing the fortified arts? The most notable reason for not going down this path is that they will probably be behind the eight ball when it comes to starting the process altogether. Good fortifieds need a reasonably comprehensive library of wines – a solera – to call upon for blending. And, that takes time – a lot of time.

“It’s a curious craft, whereby the winemaker may never see the wine released that they put down decades before,” notes Dr David Jeffery, associate professor in wine science at the University of Adelaide.

You get the distinct feeling that we are all in danger of losing this magnificent art.

It’s time to acknowledge this incredible mix of precision, patience and downright brilliance before it’s too late.

The skill and expertise required to make fortified wines is immense

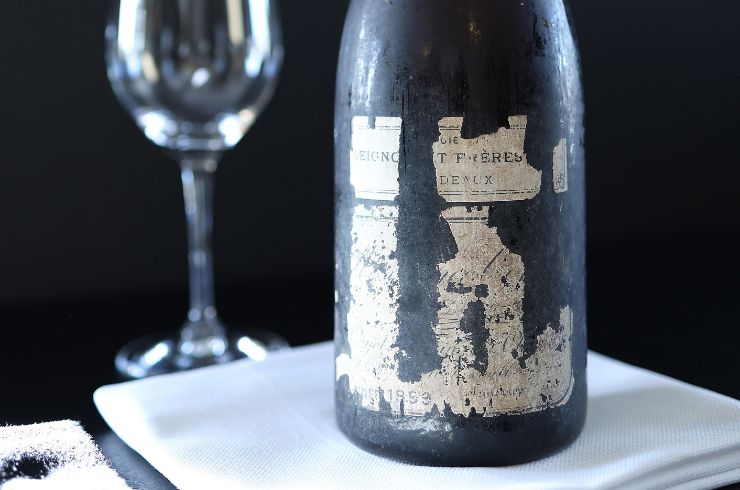

At its very best, a great fortified takes you back in time. It delivers a glimpse into the past, of past generations of winemakers, past vintages, all combining to produce something majestically surreal for today.

“Without a doubt, I believe that fortified wine making and blending requires the highest level of skill,” says Jen Pfeiffer at Pfeiffer Wines in Rutherglen.

“Just think about the process of making, ageing and blending a wine that has been matured under flor (yeast).

“The wine has almost no sulphur in it throughout its life, it is stored in barrels that are filled to only 60–70 per cent capacity, and it relies on a thin veil of yeast to protect the wine underneath. And it can be stored in this way for over five years!

“Every barrel is different, if you blend the incorrect barrels, you could introduce microbial instability in what was otherwise a very healthy barrel."

Apera (Australian sherry), sadly, isn’t exactly the poster child for fortifieds in Australia because there are less and less being made. Nonetheless, Jen Pfeiffer persists with a terrific Seriously range which deserves to be taken, well, seriously!

Tawnies remain some of the most popular fortified wines in Australia

Tawnies are a slightly different story thanks to top producers such as Penfolds and its Grandfather and Great Grandfather fortifieds; Seppeltsfield with its astonishing range of old Para tawnies; and Bleasdale’s Fortis et Astutus, a rare liqueur tawny, among others

Former long-time Bleasdale winemaker, Paul Hotker, who now works as a winemaking consultant, knows a thing or two about the discipline required for the tawny job.

“These wines are programs themselves,” he says. “They have no finish or end date but can keep going ad infinitum. Maturation of parcels spanning 50 years is not unusual – time and foresight being another layer of complexity on top of [grape] variety, spirit type, oak size, temperature, etc.”

Tawnies, like any serious fortified, require the winemaker to juggle furiously. Tawnies like to be coddled and looked after to maintain freshness. It’s a common misconception that you can leave a wine in barrel for 20 years and do nothing.

Tawnies are a sharing bunch, too, but don’t overdo it. If you’ve got just one barrel of an excellent fortified grenache left – maybe it’s just one barrel of 1985 grenache, as Hotker once had – and you use it all now, how can you blend to a consistent product again next year? You need to constantly think of the future.

And your spirit. The Penfolds winemaking team works hard on the soleras for Grandfather tawny (the solera contains trace elements dating back to 1960) and Great Grandfather (where the youngest components are around 30 years), but equally hard when it comes to the fortifying spirit. “A grape brandy spirit is selected for its distinctive aroma and flavour,” explains chief winemaker Peter Gago. “It must have the power and intensity to add complexity without presenting as the dominant character.”

The art of fractional blending (solera, muscat, topaque)

Good at maths? It will help when it comes to solera fractional blending. Makers of muscat and topaque are well practised in the art. The traditional solera involves casks stacked in layers one above each other, the youngest on top, the next youngest below it and so on.

New vintages are added to the top layer and wine moves down to the lower layers where the oldest wines are then removed for bottling, creating (hopefully) a reasonably standard flavour and style.

Today, many makers use a modified solera or blend on the bench involving other casks kept separately, adding another layer, so to speak.

On top of all that, Rutherglen fortified makers work to the four-tier Muscat of Rutherglen Classification: Rutherglen, Classic, Grand, Rare.

The Classification is reasonably specific in average years required for each blend and style. Rutherglen, the introductory level, looks to flavours of raisin, walnut and fruit cake, while Rare looks to coffee bean, aged balsamic and dark chocolate.

It’s as much a test of patience as it is precision and skill.

However, the results can be sublime – a wine of the sweetest complexity imaginable but also so fresh and alive.

“We might have the right conditions to produce a parcel of wine for a Grand or Rare in every three to four years,” explains Campbells’ fortified blender Julie Ashmead. “These new potential wines with sufficient power and fruit intensity and sweetness will spend several years in cask as a single vintage wine before being added into the solera system.”

Mandy Jones at Jones Winery & Vineyard is still working on achieving a Grand level fortified with an average age of 11–19 years which takes flavour intensity and concentration to a whole new level. It’s not easy.

“I think that might be a process that may take another five to 10 years,” she says. “Getting the right base materials with the right complexity and aged characters is the challenge on our lighter soils.”

The future of fortified wines in Australia

If it sounds incredibly time consuming and complicated, that’s because it is. It is a skill which traditionally has tended to be passed down from one generation to another, but that is happening less. And that’s a concern for the future of fortified winemaking in Australia.

Sixth generation Rutherglen winemaker Stephen Chambers, of Chambers Rosewood Winery, is rightly worried. “There are less producers of fortified and therefore the pool of knowledge is diminished,” he says.

We shall leave the last word to Jen Pfeiffer, a passionate fortified ambassador. Maybe it’s not just up to producers to fall in love again with fortifieds. Maybe wine drinkers play a role, too.

“There are some wine industry professionals who find fortifieds intimidating, because they don’t understand them, they don’t make them, they don’t drink enough of them,” she argues.

“I think I speak for all fortified producers across the world when I say I would love those people not to be intimidated by the category, but to be curious and interested."

Latest Articles

-

![Default article tile image]()

From the tasting team

Mike-Bennie-discovers-Wairarapa-NZ

11 hours ago -

![Default article tile image]()

From the tasting team

Sustainable and beyond: Marcus Ellis on sustainability in the wine industry

11 hours ago -

![Default article tile image]()

News

The reinvention of the Aussie sommelier

11 hours ago -

News

Why a co-owner of Bass Phillip decided to taste, instead of trade, this 127-year-old bottle of wine

1 day ago