Kathleen Quealy, Quealy Winemakers, Mornington Peninsula, VIC

Together with husband Kevin McCarthy, Kathleen (pictured above) is responsible for pioneering pinot grigio, and continues to explore new varieties and techniques, and produce a diverse collection of wines.

Is there anything you hoped might have changed by now?

The one thing that hasn’t changed is the participation of women. It’s still a very, very small number and that’s a real pity. I think the wine industry is missing out on a lot of skill, creativity and intelligence as a result. It would do all the men a lot of good if they had a little more competition around them.

I would like to see people appreciate that it’s not all about the winemaker. The industry is a much smarter industry than people think. I always say it’s more like a sporting team, made up of the growers, the viticulturist, the winemakers, the people who sell it, the marketers, the business side – they all contribute largely to the end product. It’s not really about one fabulous person doing it all. For us, the vineyard is king, but in Australia, it tends to come second.

The other big issue going forward will be packaging. We’ve had the big disruption where we went from cork to stelvin, so it’s possible now that can we can replace all those glass bottles with something else that’s recyclable. I think that’s just as important as what we do with the wine.

Brian Croser, Tappanappa Wines, Adelaide Hills, SA

Brian Croser, Tappanappa Wines, Adelaide Hills, SA With a long career in the industry, Brian has contributed to wine education and research, and was an early champion of the Adelaide Hills. He continues to drive new regions and sites.

How different was the industry when you first started in wine?

The Australian industry has virtually reinvented itself since I first made wine in the early 1970s. Back then, there were few wine companies and most were family owned, with roots in the 19th century. They primarily made fortifieds, although table wine was emerging. Australia’s vineyards were dominated by the fortified and distillation varieties, including shiraz, grenache, doradillo and the all-purpose sultana. From these, we made Claret, Chablis, red and white Burgundy, and riesling. Very few wines had varietal or regional definition, and there was no Label Integrity Program (LIP) to test the validity of the claims. Tiny amounts of cabernet were grown – the most revered red wine of the time – and riesling, too. There was no pinot noir, merlot, chardonnay or sauvignon blanc, and minimal malbec. They were called “exotic” varieties when they were introduced in the 1970s, and were all planted in the same “fruit salad” vineyards, regardless of conditions. So many regions were not yet planted, including Margaret River, Adelaide Hills, the Mornington Peninsula and Tasmania. Other lapsed cool-climate regions just being re-established, such as Coonawarra and the Yarra Valley, constituting half of our 65 now-recognised wine regions. Even into the 2000s, the emphasis was on branded commodity wine, affordable and widely available, now rapidly changing to Australia’s diverse and unique fine wine offerings. What a change in a working lifetime!

What do you hope still lies ahead?

That we will be recognised as the world’s premier producer of fine wine – perhaps not in my lifetime, but not too far in the future. Why do I have that confidence? Because we have a unique diversity of terroirs unmatched on any other continent. Add to that our pioneering achievements, the deference to research and innovation, and support of the peerless education of our young vignerons. In Australia, the irresistible force of human endeavour is matched by the limitless possibilities of our inherited environment.

What do you hope still lies ahead? That we will be recognised as the world’s premier producer of fine wine – perhaps not in my lifetime, but not too far in the future. Why do I have that confidence? Because we have a unique diversity of terroirs unmatched on any other continent. Add to that our pioneering achievements, the deference to research and innovation, and support of the peerless education of our young vignerons. In Australia, the irresistible force of human endeavour is matched by the limitless possibilities of our inherited environme

d’Arry Osborn, d’Arenberg, McLaren Vale, SA

d’Arry Osborn, d’Arenberg, McLaren Vale, SAd’Arry joined his family winery in 1942, aged 16, and remains active in the winery today, with son Chester heading up the business.

What are some of the bigger developments that changed the way you worked?

Without a doubt, the use of controlled yeast instead of wild yeast, which can be great, but also dangerous to the wine. There’s been a lot of research and work done as to what yeast to use, so that meant we got much cleaner wines. The minimal use of sulphur dioxide also came in when I first started, which also helped control the wine. We only had horses when I started, so it was very slow. We got our first tractor in 1947, and that was my pride and joy. Over the years, we’ve changed our system and now go through the vines much more gently. We used to work the soil a lot, which destroyed its texture and wasn’t very good for it, so that’s changed completely. Also, power came on this property in 1952. Before that we had our own lighting plant for lights.

What still excites you about the industry today?

Grenache is suddenly a great variety! We’ve always loved it, but you didn’t promote it because it wasn’t considered good enough. It was always more of a bulk wine, but dry-grown grenache makes lovely wine and it’s now recognised very strongly, and I think it’s incredible that it is.

Sue Hodder, Wynns Coonawarra Estate, SA

Sue Hodder, Wynns Coonawarra Estate, SA Sue joined this historic Coonawarra winery in 1993, and works closely with the wider team, including viticulturist Allen Jenkins, to continue its legacy.

Is there anything you expected to have changed by now across the industry?

I thought there would be great diversity of people working in wine – not just gender, but ages and nationalities. It is changing slowly, but still doesn't truly reflect Australian society today.

What do you hope still lies ahead for Australian wine?

I’d love to see more young people choose agricultural professions and lifestyles; to grow grapes, make wine and live a good life in rural Australia. This will encourage a respect for the environment – of which winemaking is a part – and help to promote sustainable practices for future generations.

This is an edited extract of an article from the February/March issue of Halliday, which is out now. For the full article, which features six Australian wine pioneers, pick up a copy or subscribe today.

Latest Articles

-

News

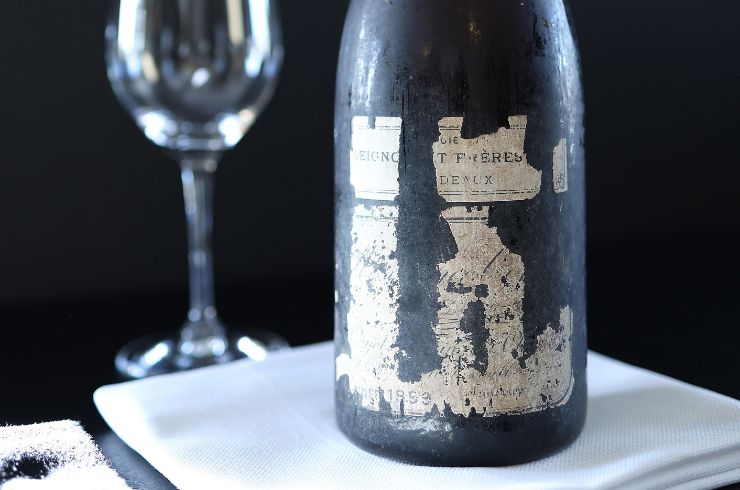

Ned-Goodwin-Romanee-Conti-1899

1 day ago -

![Default article tile image]()

Meet the winemaker

Why Hiroyuki Kusuda is one of New Zealand's most extraordinary producers

1 day ago -

Wine Lists

Discover New Zealand: seven highly rated wines from the Wairarapa region

1 day ago -

Travel

Why Clare Valley Gourmet Festival 2026 should be on every wine lover’s calendar

24 Feb 2026